As oil prices go to historic highs during this past year, energy stocks have followed a similar course. For example, front-month light sweet crude oil E-mini contract QM reached a historic intraday high of $78.30 on July 14, while the energy sector exchange-traded fund XLE reaches its historic intraday high of $60.15 on May 11. Since energy companies typically own rights to oil either above or under ground, it is reasonable that their stock prices follow the price of oil. In technical terms, we say that energy stock price “cointegrates” with the crude oil price, a concept pioneered by the Nobel laureates Robert Engle and Clive Granger. To prove that they do in fact cointegrate, I ran a Matlab cointegration package developed at University of Toledo in Ohio on the closing prices of QM (using a perpetual futures series) and XLE for the last 3 years. The program determined that they cointegrate with a 95% probabilty. Now, what this does not mean is that QM and XLE prices will always move up or down in a similar percentage everyday. This also doesn’t mean that there won’t be periods of time when the spreads between QM and XLE will go way out of sync, just as the gas futures spread did for Amaranth. What this tells us is that with high probability, the spread will eventually goes back to their historic average, and then probably goes in the opposite direction for a while.

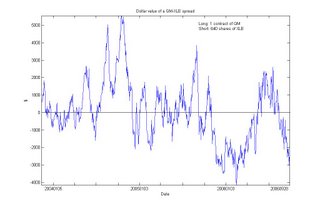

To illustrate this point, let’s take a look at a plot of the spreads between QM and XLE over the last 3 years. (Click on the graph twice to enlarge it.) Suppose we are long a front-month QM contract (rolling over the contract every month), and are simultaneously short 640 shares of XLE. The number of shares is determined by the Matlab package mentioned above. The y-axis shows the dollar value of this pair of positions. We can see that in the past 3 years, the value went as high as $5,550 on October 14th, 2004, and as low as -$4,152 on February 16th, 2006. The average is $57, which is almost zero. As of this writing (at the close of September 28, 2006), the value is -$2,584. While this is not near the 3-year low yet, it is getting there. Those who have a strong stomach will buy this spread now, and hope that the value will move back up to it long-run average of near zero. (Click on the graph twice to enlarge it.)

Some thoughtful readers may wonder whether there are any fundamental reason energy stocks have dropped much less in value since the summer than energy futures prices. Now energy companies are valued much like any other companies: roughly speaking, their stock is worth the present value of their anticipated future cash-flow plus their current net asset value. The current net asset value certainly should follow the front-month crude oil contracts very closely, in fact, more closely than their stock price. However, their anticipated future cash-flow reflects the expected price of oil in the years to come, not the current cash price of oil. (For those readers who enjoy a bit of exercise, they can look up the oil contracts that expire in 2007, 2008 and beyond to see if they in fact has higher prices than the front contract.) At this time, the stock (and futures) market is telling us this: oil price will go back up in the future.

Subscribe

Subscribe